Patents play an important role in the wind power industry and can be an important part of your company’s business strategy. This article gives you essential information about wind power industry patents so you can make informed business decisions. It can help you avoid common pitfalls and suggest best practices you can follow that can help save you time and money.

Wind Power Industry Patent Essentials

This article originally appeared in the November 2015 of North American Wind Power under the title “Patent Essentials for the Wind Power Industry.” The version that appears here is modified from the published version for this website. If you will to read the published article, please click on the button below.

The Wind Power Industry Patent Landscape

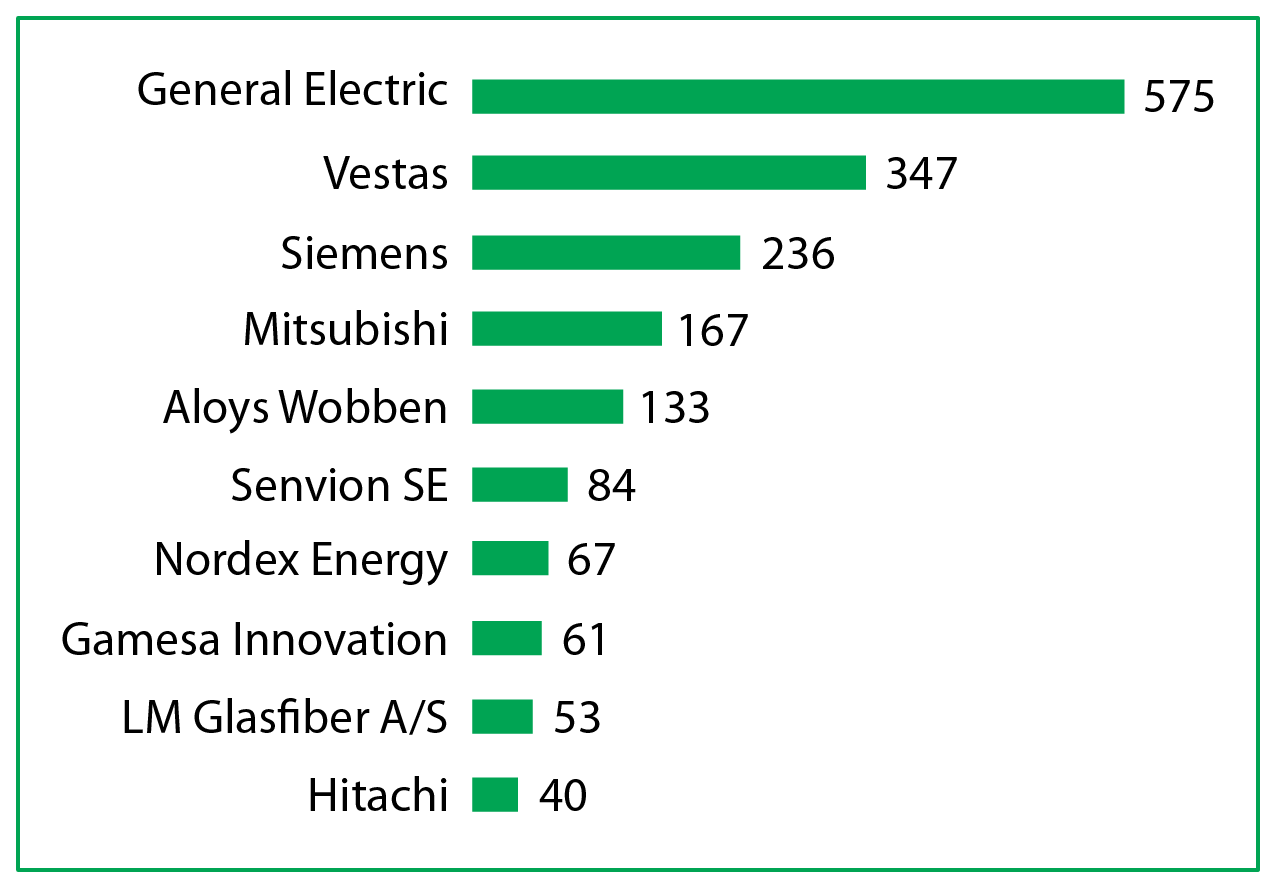

There are currently over 3,700 potentially active U.S. wind power industry patents. Ten companies own over 45% of these patents; General Electric having an estimated 575 active patents followed by Vestas with 347, and Siemens with 236 wind power industry patents. While a few large players control a significant portion of the intellectual property, 55% of patents are spread out among over 300 companies and individuals. See figure 1.

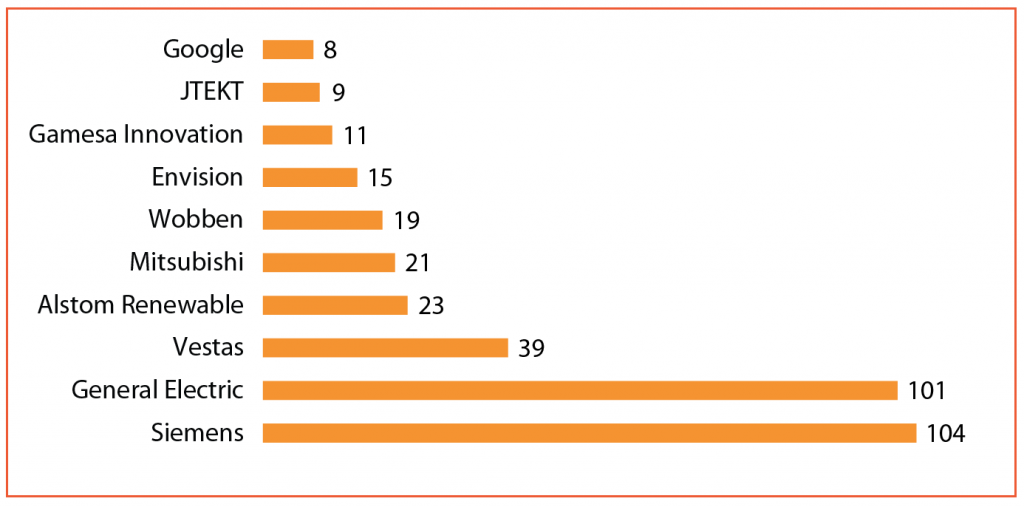

The most active wind power industry U.S. patent filers, as of 2013, are Siemens, followed by General Electric, Vestas, Alstom Renewables, and Mitsubishi. There were a total of over 290 companies and individuals filing nearly 800 patent applications. The top ten filers accounted for 45% of the patent applications filed. See figure 2. Because U.S. patent applications are generally kept secret for 18 months, 2013 is the last full year where is it possible to get an accurate picture of the patent landscape.

Understanding Patent Essentials

It is important to understand what patents are and are not. Patents give you the right to prevent others from making or using your invention. However, just because you get a patent, doesn’t mean you have a right to make or even use your patented device. Let me explain by example. Lets say you come up with a new wind turbine with a new and innovative blade design. However, the wind turbine uses a generator that turns out to be patented by another company. It is entirely possible that you could get a patent for the new turbine because of the innovative blade design, but you would not be able to manufacturer or use the device without a license from the owner of the generator’s patent. It may so happen, that the generator patent owner loves your new blade design. In that case, you have an opportunity to cross license the patents.

A patent includes a written description, drawings, and claims. While the written description and drawings describe how to make and use the inventive concept, it is the claims that define what is being patented. Claims are analogous to the legal description in a property deed. The claims stake out the exact territory of the patent.

While the drawings and written description provide context for the claims. For this reason, it is very important that you read and understand the claims of your patents.

With patent claims, less is generally better. Here are some greatly simplified examples to illustrate.

- A wind turbine, comprising:

a generator; and

a rotor rotationally connected to the generator.

- A wind turbine, comprising:

a generator including a body;

a rotor rotationally connected to the generator; and

a heat exchanger surrounding the generator body.

Claim 1 above, is stronger than claim 2. In fact, it covers just about every electrical generating wind turbine on the planet! Claim 2 requires a more specific wind turbine with a heat exchanger that surrounds the generator body.

FIGURE 2. Top ten wind energy patent owners of related U.S. patent applications filed in 2013. Because patents applications are secret for 18 months after filing, 2013 is the last full year available for reporting.

When to Leverage Accelerated Examination

The majority of wind power based patent applications are examined by four examination groups or “art units” within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. They are divided roughly into generators or “dynamos,” rotors and blades or “impellers,” control systems, and design patents. Depending on the art unit, your patent application may take anywhere from nine months to sixty months to be examined. For example, if your patent application discloses a new type of dynamo or generator, the patent application may be examined in as little as nine months. If your patent application attempts to protect an innovative rotor or blade design, your application may take two years to be examined. If you patent application attempts to protect a new wind turbine control system, it potentially could take five years to be examined. See figure 3.

In the later two cases, it might make sense to accelerate examination using a program at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office called Track One Prioritized Examination. Under this program, patent applications typically get examined in less than three to four months. You have to pay a fee to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to participate. At the time of this writing if your company has less than 500 employees, you pay $2000 in addition to the normal filing fees. If your company has 500 or more employees, than the fee increases to $4000.

FIGURE 3. The graph shows the time from filing a patent application to first examination by wind energy related U.S Patent Office examination groups or “art units.”

Consider Design Patents

So far, we have discussed utility patents. These protect function and structure. There is another type of patent called a design patent. Design patent protect industrial design. For example, if you want to protect the unique appearance of a nacelle, then you would file one or more design patents. If, on the other hand, you want to protect a unique dynamo or control system within that same nacelle, then you would file a utility patent.

Design patents have not been utilized much in the wind power industry. Currently there are just over 100 active U.S. design patents. The reason for this may be that, in the past, design patents had a bad reputation because they were often misapplied or not well understood. In addition, their scope was became limited over the years. Lately, there is a renewed interest and appreciation of design patents. In 2008 the Federal Court of Appeals in Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa restored much of the scope of design patents that had been lost. In addition, market leaders, like Apple made excellent strategic use of design patents. Rather than trying to protect the iPhone with a single design patent, Apple used a series or suite of design patents to individually protect each unique design element. Much of their litigation against Samsung was over design patents protecting, not feature or function, but the industrial design of the iPhone.

The wind power industry can take notice of Apple’s example. Strategic use of design patents can help to protect the unique appearance key aspects of a wind turbine’s structure. As an example, let’s look at figures 4 and 5. Figure 4 is from U.S. design patent D698,726 and figure 5 from D709,452. Both patents are owned by Vestas. Vestas is using these two design patents to protect their aspects of a nacelle design. D698,726 claims the appearance of the entire nacelle. D709,452 claims the appearance of the two u-shaped portions on either side of the nacelle body. Portions of both designs that are not claimed, such as the support column, rotor, and blades, are shown in dashed lines indicating that they part of the environment.

FIGURE 4. Example of a design patent for wind energy devices. This image is taken from U.S. Design Patent D698,726 assigned to Vestas Wind Systems. The design patent attempts to protect the appearance of a nacelle of a wind turbine.

FIGURE 5. Example of a design patent as part of a design patent suite. This image is taken from U.S. Design Patent D709,452. This complements US Design Patent D698,726 by focusing on the u-shaped portions of the nacelle.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

In my experience, there are common misunderstandings about patents that transcend industry. These can cause missed opportunities and prove costly.

(1) The one-year rule.

You have one year to file a U.S. patent application after any of the following events: (1) you use your invention publicly, (2) you disclose your invention publicly, or (3) you offer your invention for sale. Any of these events will start the “clock ticking.”

Public use includes hidden use. Here is an example. Say you come up with a new generator and control system design for a wind turbine. Both are hidden within the nacelle. You demonstrate the unit in a place where the public can access it. That is public use.

Your sales staff offers a customer a chance to be the first to purchase the wind turbine with the new generator design. Your engineering and manufacturing staff decide they need more time to get the unit into production and the sales order is canceled. Nonetheless, that is considered an offer for sale.

(2) Foreign filing deadlines and options.

If you are an American company and plan on filing overseas, it is very important that you understand some basic foreign filing rules.

- No public disclosure grace period: with the exception of U.S. and Canada, most countries do not have a public disclosure grace period. If you have not already filed a U.S. or foreign patent application before you publicly disclosed your invention, you loose your right to obtain a patent in most foreign countries. What public disclosure means varies country by country and is beyond the scope of this article. For example, in some countries hidden use is not considered public disclosure. You should check with a patent attorney or agent who is familiar with the patent laws of the country you are interested in filing for more details.

- Understanding PCT Applications. A PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) patent application is essentially a placeholder. It extends the 12-month foreign filing deadline typically to 30 months. PCT applications do not great into patents. However, they do get the benefit of a search and opinion by an international examiner that could be taken into account when the foreign application is filed.

(3) Provisional patent applications

Provisional patent applications have their place, but generally are a bad idea. They can lull you into a false sense of security and overall will cost you more money. Let me demonstrate by example.

Your company develops a new wind turbine with several patentable innovations. You have an upcoming tradeshow. Although the turbine still requires some tweaks, product management, engineering, and sales are anxious to show off the new turbine. Your product manager would like to be prudent and file a patent application before showing the product. She reasons that she can save time and money by filing a provisional patent application before the show. Your engineering team quickly throws together sketches, engineering drawings, notes, and other documentation and you file a “quick and dirty” provisional patent application.

Six months later, your engineering team finalizes the design. An essential element was discovered after the provisional application was filed. Your company now files a regular or “non-provisional” patent application. This new essential element is added as well as other design changes and improvements. Unfortunately, any claims that depend on this new material do not get the benefit or protection of the filing date of the provisional application.

Herein lies the problem. A provisional application is only useful for what it discloses. There is no magic here! A well-written provisional application takes nearly as much time and care as a non-provisional application.

(4) Understand the Consequences of the America Invents Act First to File Provision.

After March 15, 2013, the U.S. went from “first to invent” to “first to file.” This essentially means that first one to file a patent application wins. There are exceptions. If someone was to “derive” or steal your inventive concept, you do have recourse, and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has a procedure to address this. However, the procedure, called a “derivation proceeding,” is new, complex, and potentially expensive.

(5) Don’t Skip the Patent Search

Filing a patent application without a patent search is like driving a car down a road blindfolded. You wouldn’t do that, right? A patent search can save you time, money, and avoid wasted effort. A good patent search can spare you staff time and expense pursuing the unpatentable. It can also help your patent agent or attorney write a more effective patent.

Best Practices

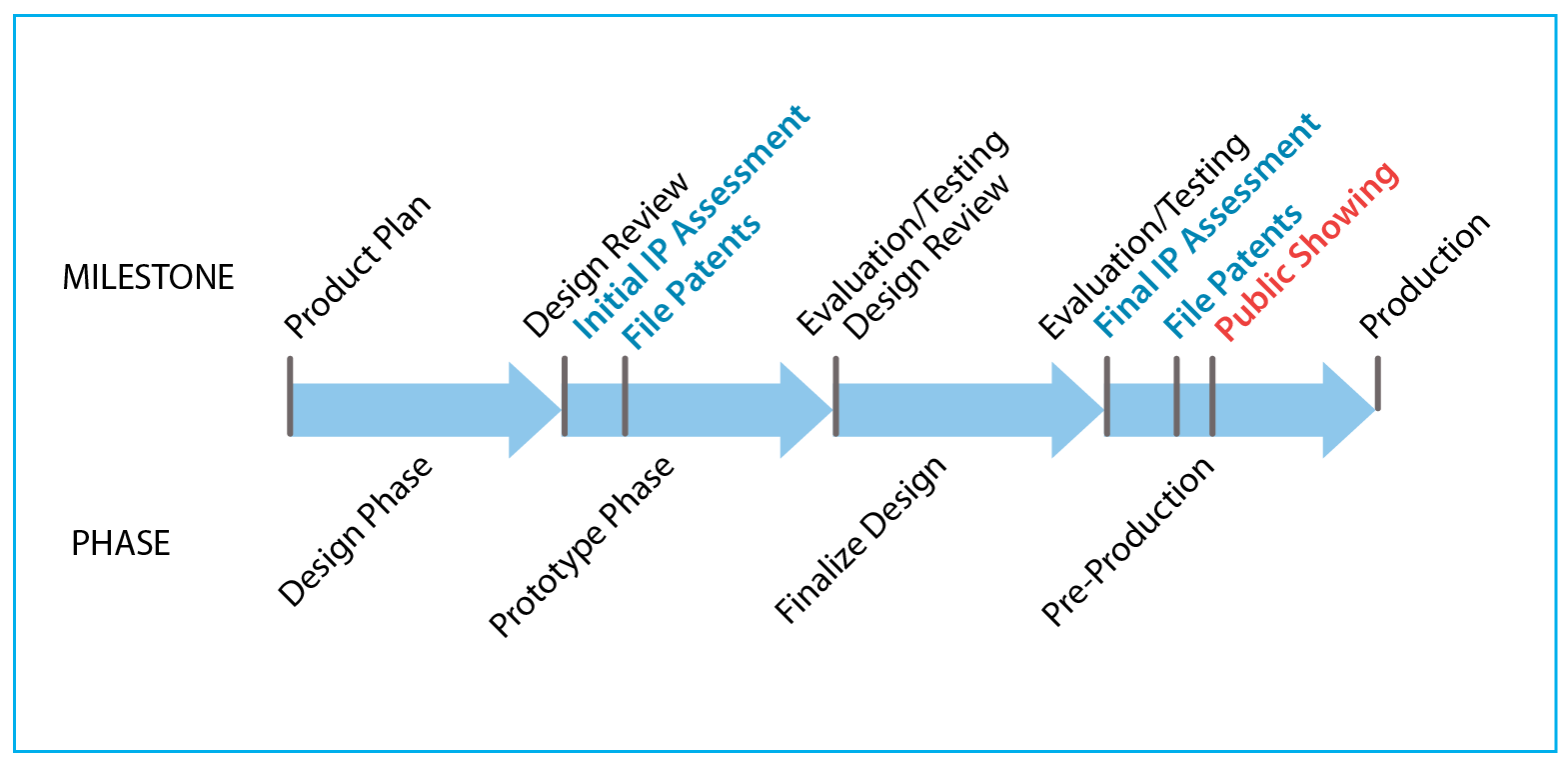

You can avoid the pitfalls discussed above by building patent protection into your product development process. Figure 6 shows a simplified product development cycle, with intellectual property assessment, and patent filing as built-in milestones or tollgates. Ideally, you should conduct an intellectual property assessment as part of the initial design review. This review should include possible patent stakeholders such as engineers, product managers, or sales managers. You may also want to include your patent attorney or agent in this meeting. A good patent attorney or patent agent can help identify commercially significant inventive concepts that may otherwise go unnoticed. For example, when I was an engineering project leader at Sony, we ended up with ten patents on one particular product. By asking the right questions, our patent attorney helped us identify a patentable feature that the engineering team overlooked. That feature turned out to be very attractive to customers and produced the most commercially valuable patent for that particular product.

An ideal time to start the patent process, for those inventive concepts that are well developed and not likely to significantly change, is immediately after the design review. Because in the U.S. first to file is the law of the land, there is an impetus not to wait.

Here are some recommended steps for starting the patent process after you do your initial patent review: (1) having the inventor write a patent disclosure, (2) accessing the potential commercial value of the patent, (3) doing an informal patent search internally, and (4) engaging your patent attorney or patent agent to do a formal patentability search.

You can incorporate a final patent assessment after the prototypes are built and the design concepts are finalized. This would now be the ideal time to start the patent process for any remaining inventive concepts including those that were not developed enough to file after the first design review.

It can be very helpful to designate a person as patent program leader or “patent champion” to lead and drive the patent process within your company. This person acts as liaison between your patent attorney or agent and your inventors.

FIGURE 6. Simplified product development cycle with an intellectual property (IP) assessment and patent filing built-in as milestones.

Interested Protecting Your Wind Power Industry Patent?

Fill out our contact form, email, or contact me by phone to set up your free initial consultation.

Call toll-free: (877) 707-1572 anywhere in the U.S. to discuss design patents.

Call: (503) 719-8905 in Portland, Oregon & Vancouver, WA area to discuss design patents and your company’s industrial designs